As 65,000 fans lined the Mall for the England Women’s victory parade last month, one supporter held up a sign: “1921: ‘Unsuitable’. 2025: Whatever!”

The meaning was clear: on 5 December 1921, the Football Association (FA) announced its decision to ban women from playing at FA-affiliated grounds, stating that “Council felt impelled to express the strong opinion that the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and should not be encouraged”. More than a century on, the Lionesses had once again proved the FA wrong.

As sports historians have explained, reasons for the ban included misguided concern for women’s (and the nation’s) reproductive health, claims that the funds raised by charity matches were being mismanaged, and even jealousy about the growing popularity of the women’s game.

But behind apparent anxieties about women’s participation in “the most vigorous of manly games”, as the 8 December 1921 edition of the Leeds Mercury described it, was a greater, unspeakable fear: women and girls who played football just might be queer.

Three months before the FA’s ban, lesbianism had been the subject of a lively Parliamentary debate. On 15 August 1921, the House of Lords rejected an amendment that would prohibit “any act of gross indecency between female persons” primarily on the grounds that such legislation would draw attention to the possibility of love between women. “It would be made public to thousands of people that there was this offence; that there was such a horror”, warned the Earl of Desart. “It would be widely read. We know the sort of publicity that sort of thing gets, and it cannot be stopped”. In other words, to borrow a phrase often heard in the context of women’s sport, if you can see it, you can be it.

Two high-profile legal trials had already brought the hazy idea of love between women into the British public consciousness. As Jodie Medd has argued, the “Cult of the Clitoris” scandal of 1918 and Radclyffe Hall’s 1920 slander case represented “a discursive conjuring up of lesbianism as a ghostly possibility—incoherent, undefinable, diffuse, mobile, evasive, shaped by its invisibility”. Lesbianism was very much in the air, lurking behind the vague language of “vicious women” and “grossly immoral” behaviour.

Meanwhile, sexologists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had been clear on the association between sexual difference in women and a liking for “manly” pursuits. In Psychopathia Sexualis, first published in 1886 and revised and expanded in subsequent editions, German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing observed that “Uranism [or homosexuality] may nearly always be suspected in females wearing their hair short, or who dress in the fashion of men, or pursue the sports and pastimes of their male acquaintances. […] The masculine soul, heaving in the female bosom, finds pleasure in the pursuit of manly sports, and in manifestations of courage and bravado”.

It was against this political, legal, and medico-scientific backdrop, and amidst rising moral panic, that the FA declared football “quite unsuitable for females”. Although FA officials are unlikely to have encountered sexological theories, they would have been all too familiar with players’ “manifestations of courage and bravado”.

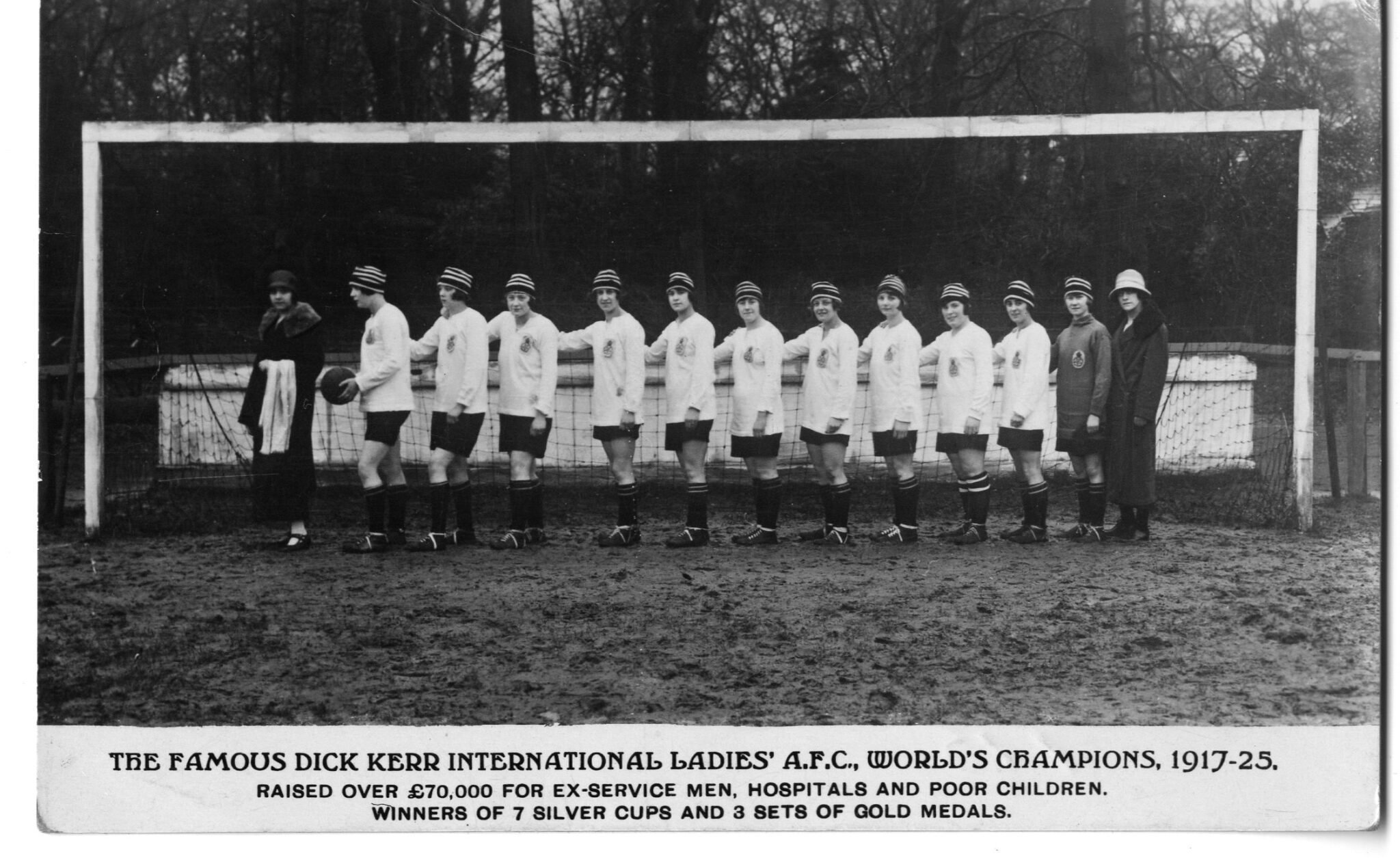

Over a hundred years before Lucy Bronze revealed that she had played all six matches of the Euro 2025 tournament with a fractured tibia, trailblazer Lily Parr fired a shot so powerful that it reportedly broke a male goalkeeper’s arm. Parr, who played for Preston’s Dick, Kerr Ladies, the most successful of the many teams made up of factory workers during the First World War, embodied sexology’s “amazon” with her inclination for “manly sports”. She is now celebrated as a queer pioneer.

In 1921, hostility towards the women’s game was nothing new. When the British Ladies’ Football Club was founded in 1895, with aristocratic feminist Lady Florence Dixie as its president—whose older brother was the 9th Marquess of Queensberry, famously sued for libel by Oscar Wilde—journalists complained about the public’s “curiosity to see women do unwomanly things” (London Evening Standard, 25 March 1895). But in a postwar context of national unease, Parr and her teammates’ very visible physical strength risked making the link between an “unwomanly” game and sexual otherness far too obvious.

It was not until 1928 that another famous ban would at last give the figure of the lesbian a very public face. Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness, condemned as obscene for its sympathetic portrayal of “unnatural offences between women”, brought sexology’s “sexual invert” to life. The novel’s protagonist, named Stephen because her parents longed for a son, is sporty and athletic, and she considers her muscular body “a thing to be cherished, a thing of real value since its strength could rejoice her”.

Stephen is a fencer rather than a footballer, but Hall was well aware of the relationship between certain sports and queerness. A year and a half before The Well’s publication, she had written a provocative letter to the Daily Express, asking why “nearly every recreation, sport or game, always, of course, excepting hockey and football, would seem to be infinitely more propitious to matrimony than golf” (“Girl Golfers Who Shun Marriage”, 7 February 1927). Though Hall brings golf to the fore, readers might ponder why football is, “of course”, not a game that will lead to marriage. (Her draft reveals that hockey was an afterthought.)

A glance below the line of recent tabloid articles on the Lionesses’ “BAPs” (Boyfriends and Partners) shows that women’s football continues to trigger both misogyny and homophobia. But the game has a long history of resilience and resistance, and today’s tiresome comments about “manly” women are even less original than we might think.

For more information on this topic, visit these sites:

https://www.thefa.com/womens-girls-football/heritage/kicking-down-barriers

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17460263.2020.1726441#abstract

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/23472/summary

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781403984425_12

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.200360/page/n417/mode/2up?view=theater

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/55884099

https://www.dickkerrladies.com

https://www.thepinknews.com/2021/02/14/lily-parr-lesbian-footballer-football-lgbt-history-month

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-south-scotland-66232240